When I arrived a little too late on deck, Ceylon lay already only a few miles in front of us, so that we could clearly distinguish the palm tree woods at the coast on this beautiful morning. Clam, who had been up on deck since dawn, said to me that Adam’s Peak too had been a spectacular sight when it became visible between the suddenly parting clouds. I could unfortunately not partake in this view as, in the mean time, shrouds of mist covered the horizon again.

Numerous boats with Sinhalese approached us shouting “Hossani” and encircled our ship while it entered the harbor. These boats are of the most adventurous form. For the primitive requirements of the Sinhalese boatmen a hollowed out tree trunk is sufficient, a sort of canoe on whose side is fixed a strong post with poles in order to keep the balance. If they use a sail, one of the boatmen shifts to the post to handle it from there. It is beyond belief how many persons can be carried on such a vehicle and how skilfully the Sinhalese manage to operate it. For short distances, they only use four linked posts which are set in motion by a board-type rudder. As totally similar boats are used in the South Sea islands, it is believed that this supports the conclusion that the Sinhalese are descended from the South Sea islands.

Colombo, the capital and the most important harbor of Ceylon has seen an extraordinary development since the British have occupied this island (1802) so favored by climate, vegetation and commercial location.

This can be measured by the current production, culture and trade relations of the island of Ceylon, once called by the old Taprobane and Singhala by the Indians. The island has a surface of 63.976 km2 and according to the census of 1891 3,008.466 inhabitants. The English blue books list the exports of Ceylon in the year 1891 as 51,449.772 fl. in Austrian currency the imports as 58,305.960 fl. in Austrian currency. The ship traffic in Ceylon’s harbors (Colombo, Point de Galle, Trincomali etc.) amounts to 5,696.940 t during the same year.

In the harbor of Colombo lay many large postal and passenger steamboats, multiple transport ships, one English gunboat and a Russian vehicle. As soon as we had anchored, we were greeted by the usual territorial salute which was answered by the land battery.

Then came our consul general in Bombay, Mr Stockinger, on board to join me for the duration of the journey in Ceylon and India and to present me with a large program organized by the governor of Ceylon. Shortly afterwards, governor Arthur E. Havelock presented himself, together with an adjutant. This highly educated man, having invited me to visit Ceylon and especially to an elephant hunt, knew many interesting facts about this majestic island and namely about Kandy to which he added reminiscences of his prior posting in Natal in a most attractive manner.

Shortly afterwards arrived Kinsky too who had been sent on a reconnaissance mission to India to prepare the journey across that country. Kinsky came directly from Calcutta and had suffered from bad weather during the whole passage to Colombo so that he arrived later than expected. He would from now on be, like Stockinger, part of our travel expedition.

To return the official visit of the governor I went on land where I was met at the landing bridge by the governor, the dignitaries of Colombo as well as a number of representatives of the native community. There was also a splendid looking honor guard of the 6th English infantry regiment present with beautiful tall people in fitting white tropical uniforms.

After I had inspected the honor guard, the governor presented me a number of native notables, then military dignitaries, churchmen, judges and other civil servants. Communication was restricted to silent hand gestures as I did not have sufficient command of English for a full conversation.

Through a sort of porta triumphalis made out of palm leaves, coconuts, pineapples, blooming flowers etc. with an inscription welcoming me we arrived at a four-horse governmental carriage which was escorted by a guard mounted on Australian horses. With their beautiful uniforms, the long lances and the colorful turbans, these choice soldiers looked very martial.

Behind the troops in line stood end to end, closely packed, a huge crowd – Englishmen, Sinhalese, Indians, Afghans, Malays wildly mixed together – greeted me with waving kerchiefs and inarticulate sounds. Especially my green wavy plume of feathers proved to be the object of curiosity for the Sinhalese youth as the boys of Colombo shouted, pointed and gesticulated at it with their fingers without interruption.

The guard of honor was ordered first by the regular military forces, namely infantry and artillery, then native artillery. The whole road was festively decorated.

After we had passed three more triumphal arches we finally arrived step by step at Queen’s House, the government building in which the governor does not reside as he spends all the time of the year at Kandy. This airy building, suitably adapted to life in the tropics, is reserved for festivities. A small ethnographic collection and delightful fresh flowers graced the reception room and the veranda from which we looked out into the garden which offered a glimpse of the wonder of the tropical vegetation we were bound to see during the following days. There stood a huge Ficus religiosa, yonder coconut and fan palms had put down their roots. Juicy green banana trees stretched their broad leaves into the air, Tamarix presented themselves covered in lianas, and everywhere gleamed the most beautiful and colourful flowers and blooms amidst which flew glittering bulbuls and frail butterflies.

In Queen’s House, I made the acquaintance of my newly recruited Indian servants, dark colored persons with long beards in a beautiful livery shot through with gold and covered with monograms. They were to accompany me during my whole time in India.

After we had changed our clothes, Sir Arthur E. Havelock had us served delicious refreshments, among them pineapple and mango fruits. We then made a sightseeing tour of the city with his adjutant Captain Pirie starting with the museum lying at one end of the city.

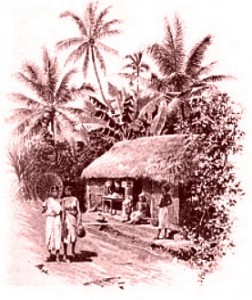

The most varied, interesting and strange impressions overwhelm the newly arrived on this journey. I didn’t know where to look, where to keep and where to stop looking. In the beginning I felt rather apprehensive and overwhelmed. Only with time, I managed to collect myself to observe and appreciate. Amidst the most luxurious tropical flora, the most beautiful and highest trees stood houses, bungalows, of the Europeans and the airily built huts of the Sinhalese. The Europeans living here, mostly Englishmen, most often civil servants and also some merchants, improve the surrounding of their houses with small gardens, an endeavour nature assists most willingly in this glorious climate.

The huts of the Sinhalese are poor. The people themselves are of a frail stature, also, it is said that they are not very industrious but of good nature. It gives the impression of big children living thoughtlessly from day to day. The clothes of the Sinhalese consist of the Sarong for the men, a large piece of red or white cloth which they wear around their waist while head, body and feet remain mostly naked. The women use beside the named Sarong a white cover or a picturesquely arranged cloth which they tighten as soon as a European is approaching. Children use as their only garment a small silver chain with a tiny heart or other amulet.

The facial expression of the Sinhalese is not nice; during my stay I could not discover a single pretty face among the women. The Sinhalese marry very early at the age of 12 to 14 years, are monogamous and are blessed with many children. The children are carried up to their fifth or sixth year by the mother, and namely by a peculiar manner in that they sit on the mother’s hip bone or more precisely, ride on it.

In front of the museum is a bronze statue of its creator, Sir W. Gregory who was governor of Ceylon from 1871 to 1877.

The ground floor rooms of the museum contain a rich ethnographic collection from all parts of the island of Ceylon, delicately crafted jewelry in gold and silver, different sets of weapons and knives, a large collection of grotesque masks that the natives use in their devil’s dances. In one of the display cabinets are healing masks with hideously distorted faces which, as a guide explained to me, are placed on the sufferer’s face to chase away the evil spirits and thus heal the patient. Depending on the type of illness, different masks are used. Particularly horrible is the grotesque mask against toothache which leaves no doubt about the artist’s intention to chase away the demon causing the pain. Whether he was successful, I could not obtain certainty about, otherwise I would have convinced a Ceylon dentist to practice his painless dentistry in Vienna to the benefit of suffering mankind, in spite of laughing gas and dental fillings. Also the numerous ship and boat models caught my attention as well as the rich clothes and the products of the Sinhalese local industry.

In the rooms of the ground floor one finds stone inscriptions on the walls whose origin is dated to the third century BC, colossal lions cut from stone, one of whom originating from Polonnaruwa is said to have served as a royal throne. Skillfully chiseled portal beams and other fragments of the temple of Anuradhapura and more.

Of particular interest were two models of which one represented a man the other a woman of the Vedda tribe which lives in the deepest jungle of Northern Ceylon, part of the original native population before the Sinhalese immigration and on the way to extinction. Also there are primitive weapons and other objects used by the natives. The savages themselves can almost never be observed. In an almost sick dread against all kinds of observation they know how to avoid to meet foreigners even for trade occasions on which they from time to time depend upon. Thus the natives deposit their trade objects – wild game – during the night at certain places in the woods which the Sinhalese recover by day and place their own trade objects of iron, cloth etc. there.

The first floor of the museum contains the zoological collection which consists solely of specimen from the fauna of Ceylon. Among the native species of birds I found so many animals that are common in Europe too. Especially numerous and in the most peculiar and colorful varieties are the genera of pigeons, kingfishers and water foil in general. Among the mammals, two genera of panthers as well as two different snake-eating types of mongoose with a strong resemblance to Ichneumon attracted my attention. A rich collection of butterflies forces even the layman to admire it.

After the museum visit we continued our trip through the most beautiful parts of the European city and the native quarters to the quay bridge. Streets according to our common understanding with closely arranged rows of houses exist in Colombo only straight at the edge of the sea and even then in limited numbers. In return, the city of 126,926 inhabitants ranges out park-like for many miles into the countryside.

The houses in the streets at the beach serve as shops and bazaars on the ground floor in which work and trade Sinhalese, Afghans and Muslims immigrated from India. The last group are easily recognized by their pudding-formed head covers made out of straw and are notable for their intelligence. They have managed to attract most of the trade business.

The Portuguese rule of Ceylon (1505 to 1656) lives on in many family names of the Sinhalese whereas the so called Burghers, mixed blood of Dutch and natives, are a reminder about the time of the Dutch occupation of the island (1656 to 1802). This is visible at a glance as the Burghers, while otherwise clad in oriental style, invariably wear a cap that resembles those worn by Dutch peasants. The only occupation of the Afghans is as knife grinders. The Tamils, people from Madras, perform the heavy lifting duties. All life is acted out on the street and like a kaleidoscope the turmoil and throng of the people is passing us by.

At noon, having returned on board, I received the members of the Austro-Hungarian colony, completed the letters to be sent home and went back on land again to do some shopping together with consul general Stockinger.

Towards evening a giant coach with four Australian horses, guided by Captain Pirie, led us to the 11 km distant Mount Lavinia, a resort the inhabitants of Colombo love to visit to catch the fresh air and sea breeze.

The journey of an hour is very picturesque. First one passes many small ponds, crosses bridges that fly over creeks and brooks and then traverses cacao and cinnamon plantations whose intense aroma discloses their presence from afar. These are encased by impenetrable high hedges of cactus-like Euphorbias, luxuriously blooming ferns, Rhododendrons and bamboo.

The excellent road continues through a never ending palm grove which offers shelter to many small Sinhalese huts. Everywhere are majestic trees, covered in lianas, such as the nutmeg tree, the mangosteen, the durian, the ebony trees (D. ebenum, D. ebenaster, D. melanoxylon), satinwood as well as the Egyptian Doum palm (Hyphaene thebaica), the Dracaena and so on. They offer refreshing shade, not a ray of the sun manages to pierce the canopy.

Close to the city, the houses of the Sinhalese are better built, mostly out of small bricks and boards, with a sharply pointed roof. The more one advances into the interior of the country, the poorer the houses become. Those are made out of clay. The land on which the house stands has to be acquired from the government. The needs of these people are small as only a small number of coconut palms are sufficient for survival so it is not surprising that the natives rely upon the blessing of heaven for their welfare and the majestic climate. A genre painter would find the most splendid subjects among the Sinhalese settlements: The whole family is lingering in front of the hut, a pater familias with a long beard at the top, at the side some old women looking like witches and furies, as well as a few young pretty women, most with a baby at their breast. The whole enclosed by the hopefully growing up youth in sweet communion with numerous dogs and cats in the sand as well as a colorful mixture of tools, pigs, zebus and empty coconuts.

The uncommon view of our coach irritated all the natives we passed; in large groups they stood and starred at us.

Lavinia is a large hotel in the European style, originally the villa of the governor Sir E. Barnes, which, situated on a bare hill, offers a beautiful view of the palm groves, the sea and Colombo in the distance. The temperature is here always a bit lower than in the city and a wonderful beach is inviting a swim. Sitting in front of the hotel, we whiled away the mild evening and enjoyed the view of the sea, the fiery picture of the sunset. The dinner partly French partly English partly Indian was notable by its colossal number and variety of dishes in which a wide range of animal and plant products with the most diverse sauces and aspic made their appearance. In our thirst for knowledge we tasted everything and had to pay bitterly for this the next day, having been used to much simpler fare during the long sea voyage.

The return drive to Colombo in the warm tropical heat was exquisite. The stars were twinkling through the palm groves, megabats flew slowly above our heads, countless brightly luminous fireflies soared like will-o‘-wisps in the canopy. Enchanted but also truly tired from the first day passed in the tropics we sunk quickly into deep sleep in our cabins.

Links

- Location: Colombo, Ceylon

- ANNO – on 05.01.1893 in Austria’s newspapers. The snow storm continues to vex Vienna. Most railway lines are negatively affected, especially international connections. Warsaw reports three cholera deaths as well as multiple sick patients.

- The k.u.k. Hof-Burgtheater is playing Georges Ohnet’s Der Hüttenbesitzer (Le maître de forges); the k.u.k. Hof-Operntheater presents a one-act opera Cavalleria Rusticana as well as a ballet Rouge et Noir.